UHCL prof highlights human rights abuses of refugees in book

February 13, 2018 | UHCL Staff

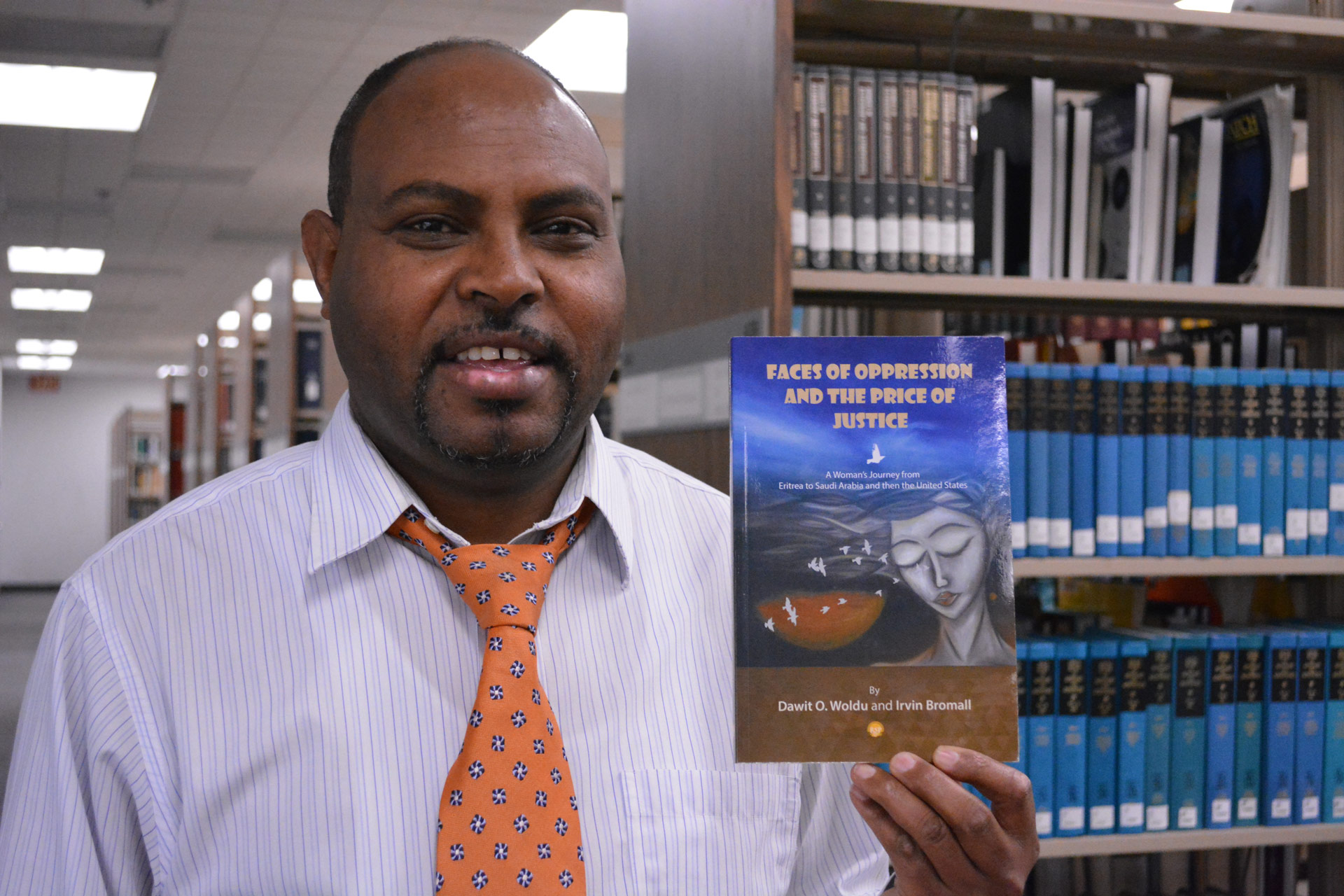

Dawit Woldu, assistant professor of anthropology and cross-cultural studies at University

of Houston-Clear Lake, would like to clear up misconceptions about how refugees obtain

asylum in the United States. He and his colleagues – Assistant Professor of Anthropology,

Christine Kovic and Assistant Professor of Applied Sciences Isabelle Kusters – will

discuss refugee-related topics on March 5 from 7 p.m-9pm. in the Forest Room of the

Bayou Building.

Woldu is an author of the newly released book, “Faces of Oppression and the Price

of Justice,” which explores the traumatic journey of an Eritrean woman’s attempt to

navigate American immigration laws to free herself from a life of abuse by seeking

asylum in the United States.

The woman, whom Woldu named “Natsanet” because it means “freedom” in Eritrea’s native

Tigrinya language, faced an impossible life decision upon her 18th birthday. It was

the same decision faced by all Eritreans, regardless of gender: Either become conscripted

in the military and endure certain rape and physical abuse for no pay, or go to Saudi

Arabia and work as a domestic servant.

“Because Natsanet chose to leave her country and become a domestic, she had to sign

a contract saying she would pay a percentage of her salary and other fees to the Eritrean

government,” Woldu said. “She ultimately became essentially the slave of a rich Saudi

family on a visa sponsorship, which means that she lost her passport and came under

the complete control of the family.”

Natsanet ended up staying five years in a situation in which she was terribly abused

– beaten, confined, overworked and raped. “The book discusses human rights abuses

in Eritrea and the country’s overall human rights standing, which ranks on par with

those of North Korea,” Woldu said. “I work with organizations to assist refugees,

and she embodies the population that I work with. Natsanet’s story was very touching

and traumatic, and that is why we decided to write the book.”

In 2002, Natsanet was able to break free from the Saudi family who had tortured her

for five years when she accompanied them on a vacation to a resort city in the U.S.

“She was confined to the hotel, and told to do some ironing,” Woldu said. “The wife

slapped her very hard, and Natsanet simply walked out the door and began wandering

in the street.”

After finally finding some help from an Ethiopian woman and her husband, Natsanet

found a lawyer who wrote a deposition that was submitted to immigration authorities

to petition for asylum in the U.S.

“Her petition was denied by the judge,” Woldu said. “She was put in deportation proceedings.

If she had gone back to Eritrea, she would have disappeared in a jail because under

the law, she was guilty of treason for breaking her contract with the Saudi employer.

She was supposed to have been sending a percentage of her earnings and other fees

to the Eritrean government. The Eritrean government would have treated her escape

from her abusive situation as a criminal offense.”

Woldu got involved with Natsanet’s case to help her raise the funds necessary to hire

a lawyer to keep her from deportation, certain imprisonment, and likely death. “It’s

a very tough legal process here,” he said. “The book highlights the impossibility

of the immigration system. People think it’s easy to get in. It’s not. And if they’re

here, they’re not home free. It’s one of the most difficult immigration systems in

the world, and it’s well organized to protect the U.S. Receiving asylum can take years.”

He pointed out that seeking political asylum is a completely different process for

refugees than the immigration process for undocumented immigrants. “Those are two

entirely separate circumstances,” he said.

Woldu explained that the term “undocumented immigrants” refers to people who either

entered the country illegally and did not apply for protection, people who overstayed

their visa and did not apply for asylum, or people who lost their asylum case and

did not leave the country.

“People who are asking for asylum need protection and cannot return to their country

because they’re in fear of their life. And there are many social, cultural and communication

factors that cause problems with lawyers and impede the process and people who deserve

protection could possibly unfairly lose their case,” Woldu said.

Natsanet’s ending is a happy one. She was finally granted asylum in 2011 and resides

in the U.S. “Her story is a way to explore the larger human rights story, the immigrants’

story,” Woldu said. “These people have a dream; they would just like to be a productive

member of society. Overall, they’re good people who need protection and want to raise

their families and save their own lives. This country was based on those ideals.”

He added that this was a moral issue for people of all religions. “If you’re Christian,

Muslim or Jewish, what would you do? If someone is at your door and needs your help,

what is the right way? This is a very human conversation,” he said.

For more information about UHCL’s Anthropology program, visit www.uhcl.edu/human-sciences-humanities/departments/social-cultural-sciences/anthropology.

About the Author:

Recent entries by

October 18 2022

Better technology transforms campus safety: Police Chief demonstrates SafeZone to students

October 14 2022

Student's skill with drones takes chicken turtle research to new heights

October 11 2022

Planting event to help UHCL restore native plants to campus, support environmental sustainability