- Future Students

- How to Apply

- Visit UHCL

- Admitted Students

- Tuition, Costs and Aid

- Degrees and Programs

- Contact Admissions

- Current Students

- Class Schedule

- Academic Calendar

- Advising

- Events

- Library

- Academic Resources and Support

- Student Services and Resources

- Alumni

- Lifetime Membership

- Alumni Events

- Update Your information

- Awards and Recognitions

- Give to UHCL

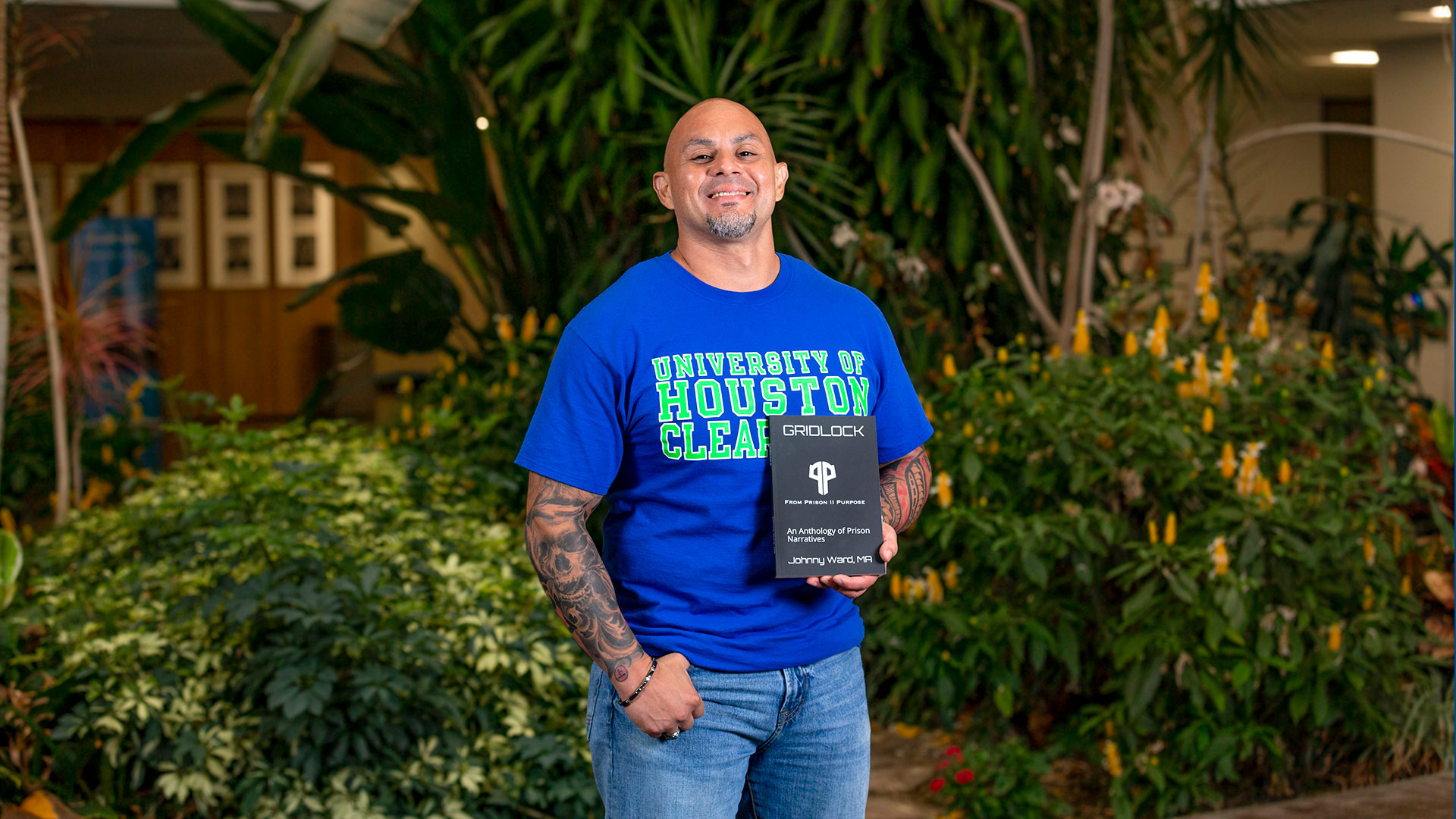

Alumnus finds path 'From Prison II Purpose'

September 24, 2020 | UHCL Staff

People don’t like talking about the “tarnished” areas of their lives. But as Johnny Ward has learned through years of painful life experience, people connect to the tarnished parts the most.

Ward earned his Bachelor of Science in Behavioral Science and his Master of Arts in Literature from University of Houston-Clear Lake while incarcerated in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s Ramsey Unit in Rosharon, Texas. He shares his journey of personal growth in a newly-released book, “Gridlock: An Anthology of Prison Narratives — From Prison II Purpose.” He will also participate in a virtual panel discussion as part of UHCL’s Common Reader program on Thursday, Sept. 24 at 6 p.m.

Ward’s book is an anthology of narratives contributed by Ward and other incarcerated scholars who were also his classmates and friends in UH-Clear Lake’s Academics for Offenders program. He was recently released on parole after his second prison sentence, in which he served over 10 years.

“I’ve only been home for 10 months, and I put this book together and published it,” he said. “I think the book gives people hope. Society sees the incarcerated as unredeemable people who fail to take responsibility for their actions. They don’t think about the people in positions of power who enforce rules in a way that is dehumanizing. I had to write about it.”

Journey to Education

Ward had a turbulent childhood. His mother was a victim of physical abuse and his stepfather, a drug dealer, kept moving the family because their home was frequently raided. “I went to 11 different elementary schools. I ended up in shelters, and homeless,” he said. “I dropped out of school in the 7th grade. I never thought about education. By the time I went to prison the first time at age 21, having already been in and out of juvenile detention, I had almost no education.”

Ward started his life-changing path toward education while in a prison transfer unit, where he was given an education achievement test. The results would indicate whether an inmate qualified for either GED or vocational courses. “I’d been out of any kind of classes since I was a kid,” he said. “When I got the results of my tests, I didn’t understand the score. I was so ashamed—it said I had a 12.9. I thought that was a percentage.”

He soon found out that the score indicated the grade level he’d tested into — 12.9 meant 12th grade, ninth month — placed him as a graduating senior, the highest high school level. “I was blown away,” he said. “I didn’t know I had any potential. I got scheduled for GED classes and got my high school equivalency diploma in two weeks.”

Two weeks later, at age 23 he headed into the prison’s junior college program. “That took me in a whole different direction,” he said. “I didn’t have any support in prison, only what I could do on my own. My education became a light.”

From the first day of classes, Ward had to figure out how to study in prison. “We had no resources at all, no one to ask questions. Some things in literature are really complex and heavy, but you’re stuck. And in a hyper-masculine, hyper-competitive environment for the people that are into academics, you have to grow,” he said. “You have to learn to deal with the fact that you’re walking to class and there would be riots going on. It’s desensitizing, but even if people died, it’s just another day.”

As the father of two young daughters, he was hoping to educate himself so he could provide for them when he was released. He finished his associate’s degree at Trinity Valley Community College in Tennessee Colony, Texas within 18 months.

When he was released from prison the first time, he was 25 and ambitious, hoping to regain custody of his daughters. “I moved to Fort Worth and started a small business in custom systems in vehicles, like alarms and TVs,” he said. “My hope was to get my daughters back from my aunt and demonstrate that I was stable enough to raise them, but Child Protective Services took my daughters from my aunt, which caused me to revert back to drug and alcohol use.”

By then, he’d married and had a son, but was battling for his custody. “My (now former) wife could see I’d been using again. She was supposed to bring my son to me and didn’t, and I went to her place and kicked her door down. I had already lost my girls. I just wanted to see my son.”

That arrest returned him to prison with a 20-year sentence. “I found myself in a bad place again,” he said. “I wanted to go back to school and show my kids that regardless of my poor choices, I could still make something productive out of it.”

A New Way Forward

In 2010, Ward applied to UHCL’s Academic Offenders program in the Ramsey Unit. “I started the bachelor’s program in behavioral science, and I started learning about human behavior, anthropology and sociology,” he said. “I started writing papers for all my classes, not just for my writing classes. I went in ambitious and was humbled fast. I learned about criminology, mental health and deviance, and learned where individual behavior comes from. I started seeing the entire world in a different way.”

When he learned more about reasons why kids don’t function in school because of the instability of their environment, he realized why he’d done so badly in school. “You can’t focus when you’re distracted by chaos in your home life,” he said. “I started to understand why I did what I did — I learned about child abuse and neglect in class.”

He also realized that he had a skill for conveying his own life lessons to his fellow inmates, and he began teaching classes about influences and helped create a manual that explores all the elements that impact people’s lives, along with worksheets and diagrams.

All his efforts paid off — he completed his Bachelor of Science in Behavioral Science in 2016 and his Master of Arts in Humanities in 2019. His time studying, reading classic literature and examining his own life compelled him to write “Gridlock.”

“This book came after the success of my Facebook page, called From Prison II Purpose,” he said. “I needed to tell the stories of the others who were still incarcerated. There were a lot of families reaching out to me through the Facebook page wanting more information or wanting to help their incarcerated loved one. I wanted to share some stories about re-entering society, and offer some direction for those who are still behind the walls.

“The book humanizes people who are in prison,” he continued. “I want to encourage people to know there are possibilities if they are persistent.”

Ward said he feels most powerful when he’s teaching others. “It’s been hard to get a job, despite my education, because my resume looks good but I have these felony convictions,” he said. “I want the end of my story to be that I’m educating the next generation of criminal justice students — people who teach this, but don’t have any experience with it. I want to tell people what it’s really about, and if the issues aren’t brought to the forefront, they can’t be resolved.”

He also hopes to write another book that provides inspiration and solutions for incarcerated people re-entering society.

Learn more information about UHCL’s Academics for Offenders program online.