- Future Students

- How to Apply

- Visit UHCL

- Admitted Students

- Tuition, Costs and Aid

- Degrees and Programs

- Contact Admissions

- Current Students

- Class Schedule

- Academic Calendar

- Advising

- Events

- Library

- Academic Resources and Support

- Student Services and Resources

- Alumni

- Lifetime Membership

- Alumni Events

- Update Your information

- Awards and Recognitions

- Give to UHCL

UHCL professor’s book chronicles tragedy of Cold War nuke tests

August 18, 2017 | Jim Townsend

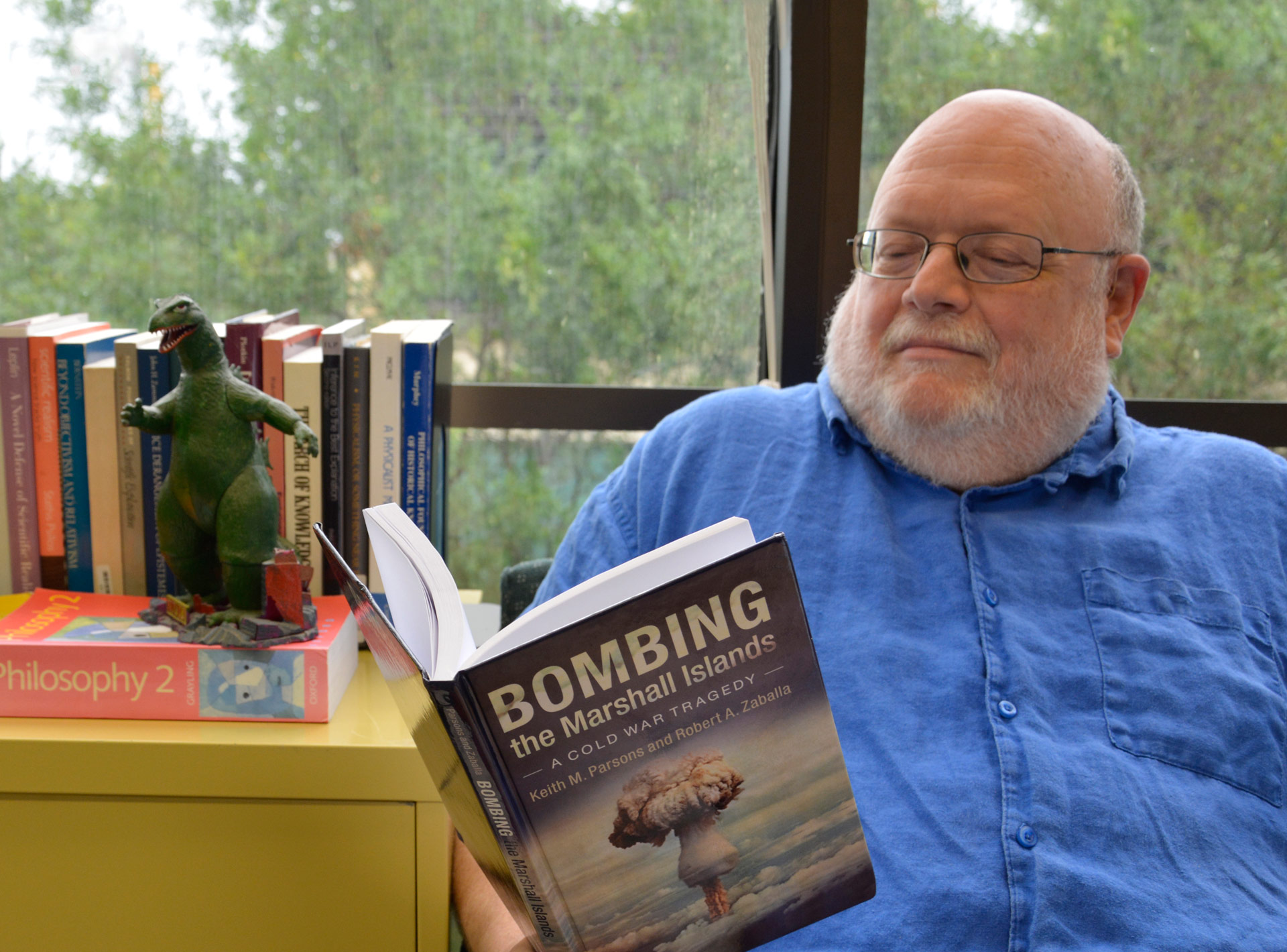

Keith Parsons, like many baby boomers, remembers the duck-and-cover drills from his childhood and has been interested in the history surrounding nuclear weapons and nuclear war ever since. Parsons, a University of Houston-Clear Lake professor of philosophy, expanded on his interest and with co-author Robert Zaballa, an Atlanta-based nuclear physicist, in “Bombing the Marshall Islands: A Cold War Tragedy,” a book just released by Cambridge University Press.

Specifically, Parsons and Zaballa examined the years from 1946 to 1958, when the United States detonated 67 nuclear bombs in the South Pacific in its quest to test and create a stockpile of weapons it hoped to never use, the book says.

One test in March 1954, code-named Castle Bravo, delivered sobering lessons in the United States’ fledgling knowledge of thermonuclear physics – basically, using an atom-splitting reaction to set off a larger atom-fusing reaction. The resulting blast was 2.5 times greater than predicted – 15 megatons, or 1,000 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, nine years earlier.

Castle Bravo, the world’s first hydrogen bomb, stands as the largest detonated by the United States, as confirmed by the Atomic Energy Commission. The resulting fireball was four miles wide. Nearby islands were stripped of everything living. The mushroom cloud spanned 70 miles and punched a hole in the troposphere, which allowed radioactive fallout to be carried thousands of miles by stratospheric winds. The blast excavated a crater 250 feet deep and 6,500 feet wide. None of this had been expected, the authors wrote.

“The idea that you can control something like thermonuclear explosions in the atmosphere is a very dangerous illusion,” Parsons said. “They really believed that if they practiced sufficient protocols and protections that they could control it. But you can’t control it.

“It’s like all those 1950s movies that were made to scare people. Once you’ve released the beast, it’s out there and it’s going to go where it will go and do what it will do and nobody can predict what exactly will happen.”

More than 230 people, most of them Marshallese, died from Castle Bravo’s fallout, the book noted. Others developed cancer. Seventy-five miles east, aboard a Japanese tuna boat that wasn’t supposed to be there, 23 crewmen and the fish in their hold were irradiated. Some died soon after. The most serious symptoms didn’t occur until after the highly radioactive boat docked in Japan and the tuna was sold to area restaurants, the authors cited from multiple sources. The incident created public hysteria in Japan – a nation for which the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were still fresh wounds. Politically, it was the shot heard around the world. It brought rise to global protests and the “ban the bomb” movement.

Parsons says that these events shouldn’t be allowed to be forgotten – especially now.

“With all the developments in North Korea, it has forcibly reminded us that nuclear weapons are still a part of our world. There are still enormous stockpiles. It’s all too easy to distract ourselves, to forget that those nukes are there. The deadliest things ever invented by human beings. We need to be reminded occasionally of what these things can do.”

While the events of Castle Bravo have dissipated from public memory, film of the blast has long been part of our pop culture, especially in movies – notably, the 1964 antiwar “Dr. Strangelove,” Parsons noted.

“You see stock footage over and over again,” he said.

His book points out that in response to Castle Bravo, Japanese filmmakers created the movie “Gojira” as a powerful statement of the terror and anxiety caused by nuclear weapons. “Unfortunately, because ‘Gojira’ was the origin of the monster Godzilla, the film was never taken as seriously as it should have been,” he wrote, adding that Castle Bravo footage was also used in the 2014 remake “Godzilla.”

As one of his childhood mementos, Parsons’ UHCL office includes a plastic model of Godzilla which he built from a kit in 1964.

The bombings on and near Bikini Atoll obliterated the ancestral home of a people who were told by the U.S. government that their relocation was temporary, Parsons said, adding that the 12 years of testing resulted in an explosive yield of 108 megatons – for perspective, the equivalent of one Hiroshima-sized bomb detonated daily for 19 years.

“To be honest with ourselves, we have to take full responsibility for the things that we do – especially things that were felt to be necessary at the time. For the indigenous inhabitants of the islands and atolls, we disrupted a way of life that had existed for countless generations. The descendants are not living the way their ancestors did. Some have immigrated to the United States and made new lives for themselves. Others are still trapped in poverty and dependence. It’s a tragic thing that we have that we have done.”

However, if the superpowers had it all to do over again, they would likely make the same decisions, he said, adding that the prevailing attitude on both sides of the Cold War was that of a zero-sum notion of nuclear parity.

“If our enemies could build these, then we had to have them first,” Parsons said.

“We were in an arms race with the Soviet Union. At that time, nobody could see that the Colossus had clay feet. But it was a Colossus that seemed to be bestriding the world and threatening us. They were proceeding to develop their own thermonuclear weapons at full speed. It was a time that felt desperate.”

He added that “nation-killing” nuclear weapons changed the nature of war and what was considered to be acceptable losses – not only combatants, but civilians.

“Everybody knew that nuclear war would be an unprecedented disaster. Sixty million people had been killed in World War II. In a full-scale nuclear war, that many would be killed on the first day. Or more. It was known that it would be an unprecedented mutual cataclysm.

“Yet the people who were in charge felt that they had no alternative but to proceed full speed to develop thermonuclear weapons and to test them. They just they just felt that there was no alternative.”

Author of several books on philosophy, religion and science, this one alone took several years to write, he said.

“I found a co-author who was a nuclear physicist, who knew the stuff that I didn’t, and that’s how the project began. I had to research everything right from the beginning. Also, I had to learn on-the-job how to really be a historian. Fortunately I had a well-known historian with a worldwide reputation who agreed to read my drafts. He gave me much tutelage and advice.

“This was probably the longest project that I’ve been on. So I’m particularly gratified to see it out in print. I think it’s a terrible story that needed to be told. Although these tests were highly publicized at the time because of the terrible things that happened, now they’ve been largely forgotten.”